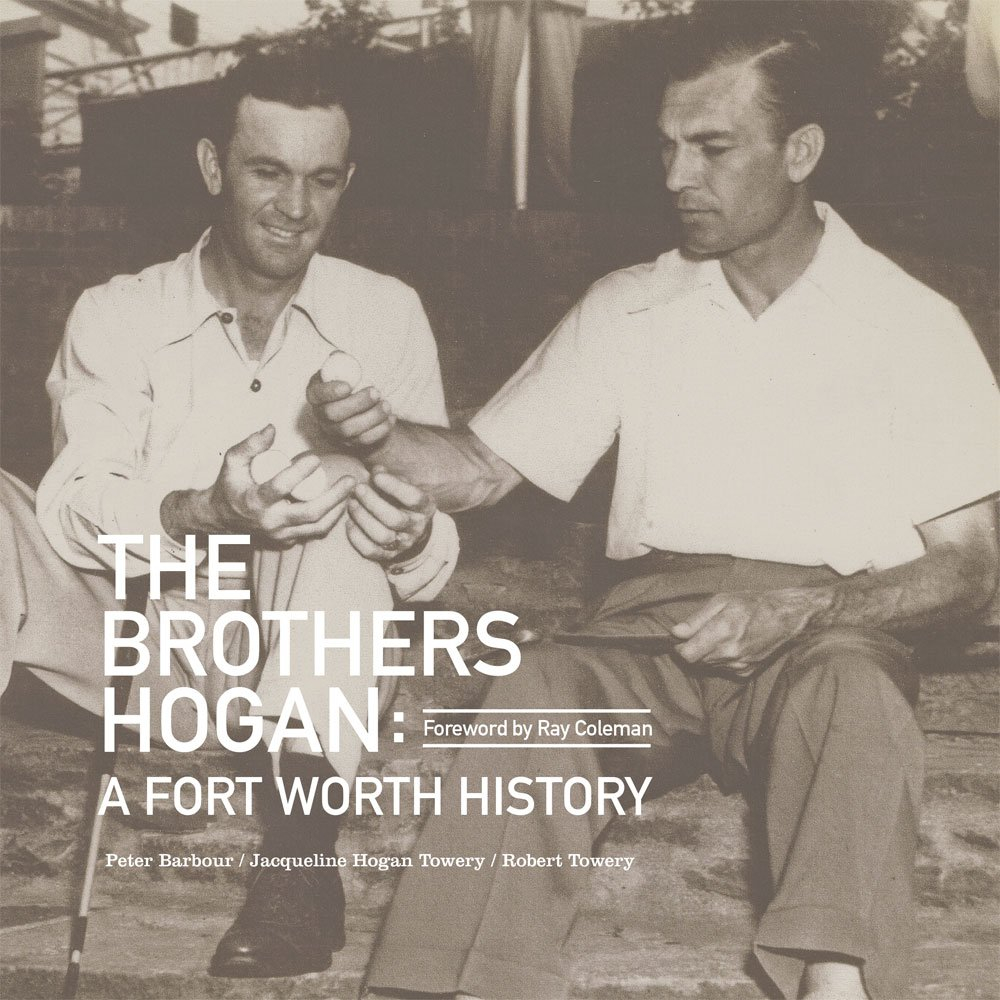

The Brothers Hogan: A Fort Worth History

Editorial Reviews

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Brothers Hogan

A Fort Worth History

By Jacqueline Hogan Towery, Robert Lindley Towery, Peter Barbour

TCU Press

Copyright © 2014 Jacqueline Hogan Towery and Peter Barbour

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-87565-596-3

Contents

Acknowledgments,

Introduction,

A Point in Time,

Panther City to Cowtown to Boomtown,

The Early Years,

Two Brothers Come of Age,

Mr. Marvin,

Family Golf,

“This Thing Is Legendary”,

The War Years,

Near-Fatal Accident,

“His Legs Weren’t Strong Enough to Carry His Heart”,

“If Used in an Office, We Have It!”,

The Hogan Slam,

The Ben Hogan Company,

Shady Oaks and the Hogan Brothers,

“Golf Is Played with White Balls”,

The Final Years,

Appendix: Hogan Family Ancestry,

Bibliography,

Index,

CHAPTER 1

A POINT IN TIME

On February 13, 1922, Chester Hogan boarded the Frisco in Dublin, Texas, and rode the train seventy-five miles northeast to the Texas & Pacific rail station in Fort Worth. In an attempt to satisfy his wife that he would search for a job once again, Chester had agreed to come to the big city to look for work. Yet, all the while, it was actually his sincere hope to bring his family back with him to their home in Dublin. It had been six months since his wife, Clara, had convinced her husband to relocate to Fort Worth and look for better opportunities for their three children. Also, she hoped this would help her husband since Fort Worth was the nearest city with a hospital capable of treating his recent, increasing bouts of melancholy. He originally came with Clara when the entire family made the move in August of 1921, but after a couple of months, in which he could not find work, he returned to his diminishing blacksmith operation in Dublin.

On this day in February 1922, after more unsuccessful job hunting in Fort Worth, Chester returned to the small frame house at 305 Hemphill Street that Clara had rented for the family. Chester pleaded with his wife to return with him to Dublin and their previous familiar routine. Clara didn’t like the idea of taking the children out of school before the spring semester was completed, however. They discussed the matter, and then argued loudly enough for the children to hear from another room. At the end of the argument, Chester stormed out and stomped down a small hallway into another room at the back of the house. His twelve-year-old son, Royal, followed him into the room.

As Chester started to rummage through his valise, Royal blurted out, “What are you going to do Daddy?”

Without answering, Chester pulled a .38 caliber revolver from his bag, aimed it at his chest, cocked it, and pulled the trigger. Clara, fifteen-year-old Princess, and nine-year-old Ben ran into the room and saw Royal standing near their wounded father, who was lying on the floor and bleeding. Chester looked up and said, “I wish I hadn’t done that.”

He was picked up by a Spelman Ambulance and rushed to Protestant Hospital. It was first thought that he would survive, but he did not. He died twelve hours later.

When reporting the suicide the next day, two of the three local Fort Worth papers, the Press and the Record, reported erroneously that a six-year-old or nine-year-old son witnessed his father’s suicide. However, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram got it right with its headline: FATHER’S SHOT IS REPLY TO BOY.

The article in the Star-Telegram went on to describe how the twelve-year-old Royal had put the query to his father right before he pulled the trigger. The report went on to quote Clara Hogan as saying that her husband had been ill for over a year, and he also had financial worries.

Clara, her daughter, Princess, and her two sons, Royal and Ben, did not discuss the incident with anyone for many, many years. But as a result of the two error-filled newspaper reports that referred to a nine-year old child being in the room, it was long assumed by many people that Ben was the child who witnessed his father’s suicide. This led to mistaken articles, and then these articles were used as references in biographies about Ben Hogan, some going so far as saying Ben’s steely disposition and hardened reserve on the golf course resulted from the fact that he had witnessed his father shoot himself. Since young Ben was in the house when the tragedy occurred, it would seem natural that an event such as this would mark a child in some way. However, his niece Jacqueline (“Jacque”) Hogan Towery, who was very close to her uncle, totally disagrees that the suicide molded his essence.

JACQUE: Mama Hogan (Clara) had a disciplined philosophy and perfectionist attitude, and it was those characteristics that had the most effect on Uncle Ben and my dad, Royal, as well. She taught them to persevere while they were growing up, especially during the Depression. Mama Hogan taught Uncle Ben and my daddy a strong work ethic that strengthened their resolve and helped make them the successful men they eventually became.

Why hadn’t Ben Hogan set the record straight?

JACQUE: Late in his life, Uncle Ben told me once, “I had been misquoted my whole career and there were also so many falsities from third person narratives, that I tired of trying to set the record straight. I decided not to deal with the misinformation, so I just let it all go.” You see, the Hogan family was very private—we just never talked about things like this. So, the people who wrote those books and reported that Uncle Ben saw his father kill himself were never informed of the mistake. To this day there are a lot of people who don’t know the real story, because nobody in the family ever talked about it. I was almost in college before I knew the story. I was told one time, and that was it. It was never discussed again.

During the waning years of Royal Hogan’s life, when he was in his eighties, his grandson, Dr. David Corley, and Corley’s wife Dayna would pick up “Pops,” as they affectionately called Jacque’s father, and take him to dinner, usually once or twice a week. They would always offer to take him to various new restaurants they thought he would enjoy, but Pops never wanted to try anything out of his element. He preferred to go to one of his staples, like Joe T. Garcia’s for Mexican food, Lone Star Oyster Bar for the fried shrimp, or his favorite late in his life, Olive Garden. Royal loved to eat their salad with breadsticks.

Dayna related, “At dinner one night at Olive Garden, Pops opened up to us about his father. According to Pops, he thought the fact his father took his own life was because his mother wouldn’t go back to Dublin. And then, Pops said the books reported their dad shot himself in front of Ben, but he added, ‘That’s not true. He shot himself in front of me.’ He told me that story one time, but I remember it succinctly.”

David added, “When he did tell us, it was a long, drawn-out story. It was not just volunteered; it was about thirty minutes of conversation. When he finished, he was wiping tears from his eyes. I never saw more emotion in Pops than he showed that night.”

Jacque always pondered what would have happened if her grandfather hadn’t taken his life when he did.

JACQUE: One has to consider what might’ve been different if that moment in my family’s past had never happened. Would my father have become a successful businessman? Would he have quit school when he did? Would he or Uncle Ben have attended college? And, most importantly, would Daddy or Uncle Ben have ever picked up the game of golf? I wonder.

CHAPTER 2

PANTHER CITY TO COWTOWN TO BOOMTOWN

One can’t discuss the Hogan family, their friends, supporters, customers, or their importance to Fort Worth without looking at the history and development of the city itself. It appears that three years in particular became important watermarks in the birth of Fort Worth as a major city: 1876, 1902, and 1917.

After the Civil War, many future prominent citizens relocated their families from other states in the South to Fort Worth. Among these were Major K. M. Van Zandt, Captain E. M. Daggett, Thomas J. Jennings, John Peter Smith, and H. G. Hendricks. This group of five men knew the importance of having rail service and what it could bring to their small town. In the early 1870s, the Texas & Pacific Railroad (known as the “T&P”) was building a rail line from Dallas to Fort Worth, but unfortunately a company underwriting the construction went bankrupt in 1872. With that the line stopped just west of Dallas—still more than twenty miles from Fort Worth. At this point, a mass exodus brought Fort Worth down from a population close to five thousand to less than one thousand souls. One local lawyer wrote to the Dallas Morning News and said that the town was so deserted he saw a panther sleeping at a downtown intersection. After this report, the Dallas newspaper began to refer to the sleepy town to its west as “Pantherville.” The term Panther City sprang from that article and became synonymous with Fort Worth for many years to follow.

Van Zandt and the others were undaunted, however. They knew the value of the railroad and were determined to bring it to their town. These men were five of the most resourceful civic leaders in Fort Worth’s early history.

Khleber Miller (K. M.) Van Zandt, who rose to be a major in the Confederacy, had been a lawyer in Marshall, Texas, prior to the Civil War. After the conflict ended, in 1866, he moved to Fort Worth and became an attorney, a merchant, and a reluctant politician, representing the city in the state legislature for several years. Van Zandt was the president of the Fort Worth National Bank for over fifty years, and for his many valuable contributions to the city and its people, he became known as “Mr. Fort Worth.”

After the Civil War Captain Ephraim (E. M.) Daggett also migrated to Fort Worth, where he built the first hotel in the city. He purchased quite a bit of land in the area, and together with Van Zandt, Jennings, Smith, and Hendricks donated 320 acres of land south of Fort Worth for the construction of a railroad station. The city later named elementary and junior high schools in Daggett’s honor.

Thomas J. Jennings was one of the first true statesmen in the city of Fort Worth. He was a major landowner and a very distinguished lawyer, and served the state of Texas as its attorney general for several years. In his memory, the city named one of its major thoroughfares, Jennings Avenue, as well as Jennings Junior High School, after him.

After attending three colleges, Kentuckian John Peter Smith arrived in Fort Worth in 1853. He was a surveyor, lawyer, real estate magnate, and philanthropist who became known as “The Father of Fort Worth” (not to be confused with Van Zandt’s moniker, “Mr. Fort Worth”). Smith was elected mayor in 1882 and served six terms. During his tenure, he was a key figure in establishing and developing the city’s first water department and in developing the stockyards. Mayor Smith also started the independent public school system, where he taught for several years, and served as a school board trustee. He was a cofounder of the Fort Worth National Bank and was the president of the very successful Fort Worth Gas Light and Coal Company. During his lifetime, John Peter Smith became the largest landowner in the area, and donated much of his land to the city for utilities, churches, parks, and a hospital that still bears his name today.

Judge H. G. Hendricks was born in Missouri in 1819 and was a direct descendant of the Mayflower’s Miles Standish. Hendricks moved to Texas in 1845 to study law under Judge G. A. Evarts in Bonham, Texas. In 1846, Hendricks became an attorney and relocated to Fort Worth to practice law. He was later appointed a district judge and emerged as one of the most respected and revered men in the city. In his honor, Fort Worth named a roadway Hendricks Street.

Under the leadership of Van Zandt and these four men, the community organized the Tarrant County Construction Company. The capital stock was subscribed in money, labor, and supplies, and the citizens of Fort Worth pitched in and helped to complete the construction of the Dallas-Fort Worth railroad, laying the final tracks into Fort Worth proper. On July 19, 1876, people from all over West Texas flooded to the city center to see a railroad engine, the first ever to arrive in Fort Worth, pull into the Texas & Pacific depot, a small wooden structure on South Main just west of what is now Lancaster Avenue.

Once this feat was accomplished, Fort Worth never faced mass exodus again. By 1900, the city had grown to a population of twenty-five thousand. The city became the center for the shipping of West Texas beef to the rest of the nation. From 1876 to 1900, over four million head of cattle were transported by train from Fort Worth—first from the T&P station, and then, beginning in 1889, from the Union Stockyards the city had built under the direction of Mayor John Peter Smith—to meatpacking facilities in such cities as Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, and other destinations around the nation. As Fort Worth grew, so did its institutions—banks, newspapers, and local retailers, all led by its earliest movers and shakers. In 1902, the city leaders succeeded in attracting Swift and Company, Armour and Company, and McNeill & Libby, and each built meatpacking plants at the Stockyards in north Fort Worth. It was during this period that the city began to be known as “Cowtown” and really started to prosper.

New developers saw opportunity in the growing city. One of the key people in this subsequent development was William Bryce, a transplanted Scotsman, who dearly loved the city. Bryce, mayor of Fort Worth from 1927 to 1933, was a bricklayer by trade, and before the turn of the century he joined with two Denver real estate entrepreneurs, Alfred W. and H. B. Chamberlain, to develop a new suburb west of downtown which became known as Arlington Heights. Bryce’s house, Fairview, was constructed in 1893, and was one of the rare examples of Château-style homes in Texas. It featured Richardsonian arches and gabled dormers and was designed by the prominent architectural firm of Messer, Sanguinet, and Messer, who were responsible for many of the famous landmark turn-of-the-century buildings and homes in Fort Worth. Fairview, which still stands today at 4900 Bryce Avenue, was one of the first homes built in the Heights. Bryce was among those responsible for developing the Fort Worth Club in 1903 as part of the development of Arlington Heights, constructing a main building for entertaining, several tennis courts, and the city’s first nine-hole golf course. By 1911, the club members had splintered over their growth and direction into the future. The club was closed, and this division begat the River Crest Country Club and Fort Worth’s first eighteen-hole golf course, built in 1912. For those who were not allowed to join River Crest, like H. H. Cobb of the O. K. Cattle Company, another group built the Glen Garden Golf and Country Club a few miles southeast of Fort Worth on land donated by Cobb. Those two eighteen-hole golf courses survive today—both built in 1912, which just happened to be the same year Sam Snead and Fort Worth legends Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson were born.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Cowtown was growing into a city, yet it was still in the shadow of its much larger neighbor, Dallas. But little Cowtown was about to explode. In 1917, oil was discovered in Ranger, ninety miles west of Fort Worth, and subsequently in nearby Breckenridge, Desdemona, and Burkburnett. These sites came through with gushers and literally turned Cowtown into a boomtown. Speculators, operators, geologists, oil companies, mavericks, and wildcatters flooded into the city and set up business. This wave of activity started in the Westbrook Hotel. It was reported that a speculator could purchase a lease entering one side of the lobby and sell it on the way out the other side. The oil booms combined with the railroads, cattle shipping, and meatpacking plants to change the landscape of Fort Worth forever, bringing national attention to a booming city where panthers used to sleep.

CHAPTER 3

THE EARLY YEARS

Chester Hogan was twenty-three and Clara Williams Hogan was only eighteen when they started having children. Their first child was born in Dublin, Texas, on April 25, 1907. She was a pretty little girl they named Chester Princess Hogan.

JACQUE: I never heard an explanation of why my aunt was named Chester, but I suspect that my grandfather wanted a boy, so he insisted that the child be named after him. Thankfully, she was also given the name Princess, by which she would be known. Princess always leaned toward the more domestic interests when she was a youngster, such as cooking, housework, and gardening. She loved music and performed in several musicals while in school. I was told that she also did some acting in local productions. Princess was the only member of the family to attend college. While attending college, she met H. Howard Ditto, who was from a well-to-do Arlington family. In the 1920’s era, his parents were early prominent citizens of the town east of Fort Worth, and they owned and ran the very successful Arlington Seed Company. Doc, as he was called, became a doctor and he married Aunt Princess. She was destined to become an excellent homemaker and a wonderful wife.

(Continues…)Excerpted from The Brothers Hogan by Jacqueline Hogan Towery, Robert Lindley Towery, Peter Barbour. Copyright © 2014 Jacqueline Hogan Towery and Peter Barbour. Excerpted by permission of TCU Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.